Meeting Google Earth Engine.

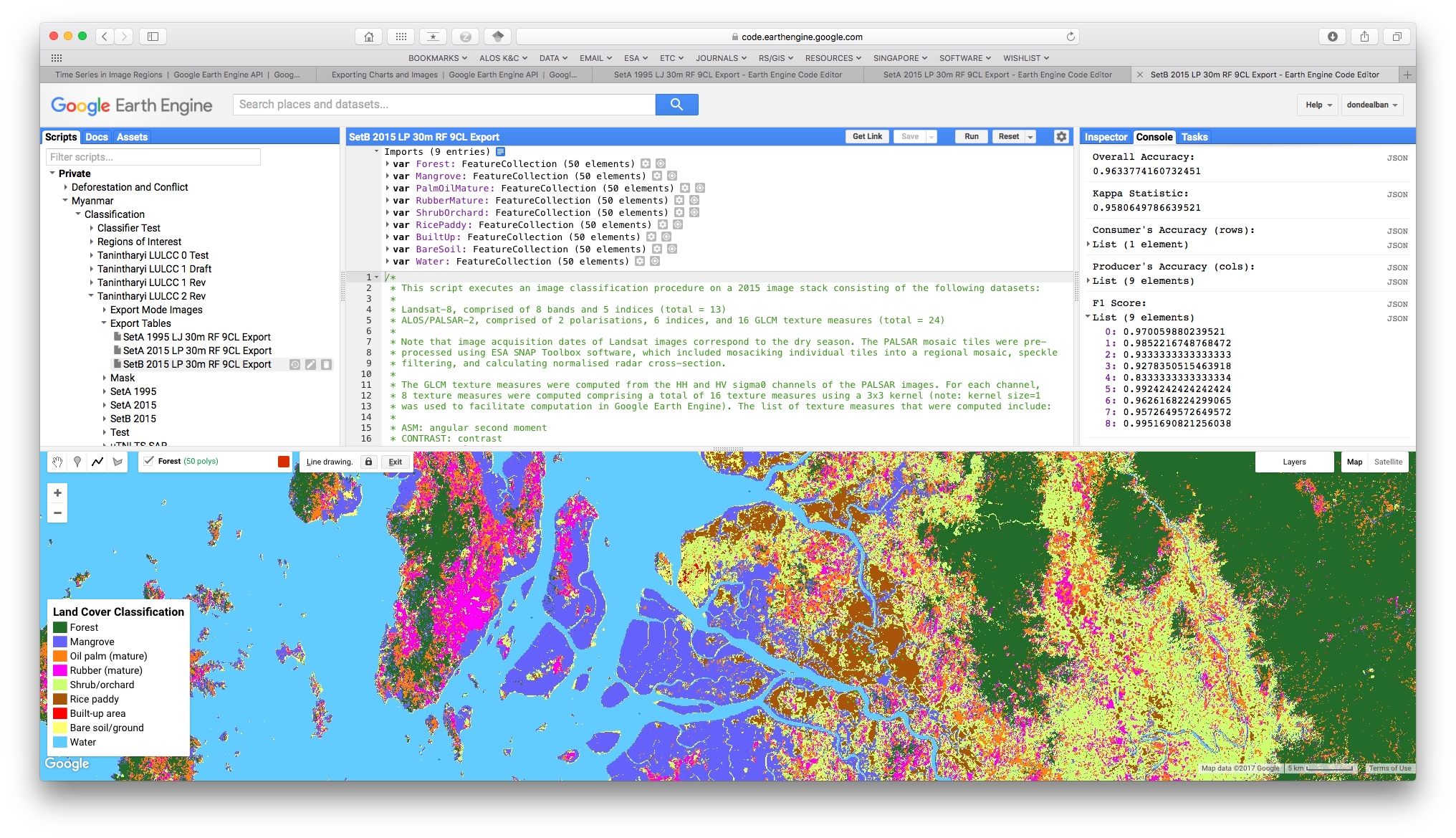

A screencap of Google Earth Engine playground. Here, I was testing my script to classify land cover types in southern Myanmar using Landsat and ALOS-2/PALSAR-2 data. The left-panel shows your script directory of your repository; central-panel your script; right-panel the console and rasks where you see your results; and bottom-panel the display of images and maps.

A screencap of Google Earth Engine playground. Here, I was testing my script to classify land cover types in southern Myanmar using Landsat and ALOS-2/PALSAR-2 data. The left-panel shows your script directory of your repository; central-panel your script; right-panel the console and rasks where you see your results; and bottom-panel the display of images and maps.

A fantastic opportunity for land change science studies in the near immediate future is the growing utility of cloud computing geospatial analysis platforms such as Google Earth Engine. Combined with the ever-increasing availability of earth observation datasets, these kinds of technologies are expected to facilitate more regional- to global-scale analyses, as well as in-depth local-scale investigations, of land system changes.

Since the latter part of last year, I have been using Earth Engine first hand for my land change analyses. To get started, I had to sign up and describe how I planned on using Earth Engine. Then once I had an account, the next step was to learn how to use the tools. The learning curve was very steep as I had to learn to code using either Javascript or Python programming languages to implement image processing tasks. But thankfully, coding can be learned with hard work, patience, and perseverance. I learned the techniques by poring through tutorials and by exploring the Earth Engine Developers Group forum, a very dynamic and helpful user community for beginners and people who wish to develop applications using the technology.

The benefits of using Earth Engine is that it overcomes the computational and data storage limitations that kept remote sensing studies in the past from realising its full potential. Previously I had to download and make local copies of all the imagery that I required on my machine, and implement all my analyses using available software tools. But I always worried about computing and storage requirements, of how much disk space, memory, and time it would take to get these done. Now, Earth Engine takes care of all these through the cloud via its parallel computing server infrastucture.

Datasets such as the entire Landsat archive and the Sentinel missions are all freely and openly accessible through Earth Engine’s public data catalog [1]. Accessing these and displaying them takes only a few lines of code without even downloading them. I’ve been able to complete landscape-scale analyses, which I would not have been able to do before given my own local resources. Now, I’ve decided Earth Engine should be one of the primary tools in my work.

Some examples of global-scale applications benefitting from Earth Engine include monitoring forest cover change [2] and surface water dynamics [3], and the global mapping of terrestrial ecoregions [4], among other examples. I invite you to read the paper by Gorelick et al. (2017) [1], which talks about Earth Engine in-depth, as well as a list of other noteworthy examples. And if you haven’t tried it yet, I encourage you to take Earth Engine for a spin. Trust me, you will not be disappointed.

References:

[1] Gorelick, N., Hancher, M., Dixon, M., Ilyushchenko, S., Thau, D. & Moore, R. (2017) Google Earth Engine: planetary-scale geospatial analysis for everyone. Remote Sensing of Environment, 202, 18-27. [DOI].

[2] Hansen, M.C., Potapov, P.V., Moore, R., Hancher, M., Turubanova, S.A., Tyukavina, A., et al. (2013) High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. Science, 342, 850–853. [DOI].

[3] Pekel, J.-F., Cottam, A., Gorelick, N. & Belward, A.S. (2016) High-resolution mapping of global surface water and its long-term changes. Nature, 540, 418–422. [DOI].

[4] Dinerstein, E., Olson, D., Joshi, A., Vynne, C., Burgess, N.D., Wikramanayake, E., et al. (2017) An ecoregion-based approach to protecting half the terrestrial realm. BioScience, 67, 534–545. [DOI].