Linking technology for conservation: a personal journey.

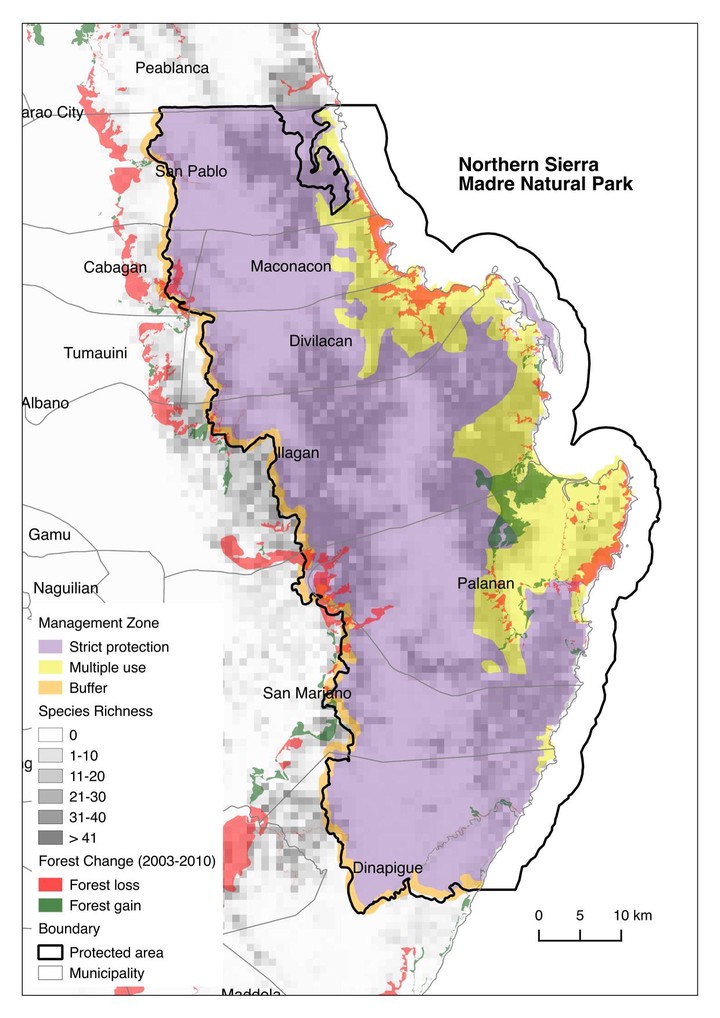

Identifying priority areas of high conservation value in Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, Philippines (from a paper presented at the 36th Asian Conference on Remote Sensing).

Identifying priority areas of high conservation value in Northern Sierra Madre Natural Park, Philippines (from a paper presented at the 36th Asian Conference on Remote Sensing).

I read a recently published review paper by Pimm et al. regarding emerging technologies to conserve biodiversity [1] in the journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution. It provided a good summary of the challenges and opportunities that came with new technologies that have been improving conservation efforts and helping to solve species and habitat loss. The authors posed outstanding questions, of which some were very relevant to my own work on conservation geomatics, most notably on combining remote sensing of environments with species distribution data and photographs of species that would allow rapid responses to threats; broadening outreach to those who collect data on endangered species and ecosystems and sharing the results with them; and filtering large amounts of data relevant for analysing and processing key questions. One of the authors, Professor Zoe Jewell of Duke University, stated [2]:

New technologies offer enormous potential for wildlife conservation. But we face a broad challenge in harnessing these technologies. We must increase the pool of data collectors, find better ways of managing the resulting huge increase in data generated, and use interdisciplinary approaches to develop creative solutions to meet anticipated future challenges.

It was a timely read that helped me rethink and reflect of the interface of technology and conservation, and of the emerging perspectives I needed to keep in mind as I moved towards the direction I was headed.

My commitment to conservation did not really begin with a fascination for the natural world when I was a child. Neither was I aware of the world’s immense biological wealth and the ever increasing threats to it, nor the pressing global conservation issues even in my college days. Rather it began shortly after finishing my undergraduate degree and I got involved in a research project through the university. In that project, I was part of a team that mapped coastal habitats using remote sensing data, and the maps and information we generated fed into improving the government’s fisheries management efforts.

What really set me along a conservation career path was my first job with a conservation organisation. I was fortunate to be part of a multi-disciplinary team that introduced me to the different aspects of conservation. It was through them that I learned that solutions towards achieving conservation success needed to be grounded on good science, led to empowered communities, and considered human well-being. It was here that I became genuinely concerned about the state of our environment and biodiversity.

The conservation challenges were many: habitat loss, illegal wildlife trade, competing resources uses for development, and now much recently, climate change. I was tech-savvy and being an engineer-geographer, I thought, perhaps my contribution to help in achieving long-term positive impacts on biodiversity and human society can be finding viable technical solutions, particularly using geospatial technologies, to address these conservation problems. I then took a keen interest and focus on utilising geospatial tools and approaches for conservation applications.

Since then, my work entailed developing and demonstrating spatially explicit methods using remote sensing and geo-informatics such as to analyse competing resource uses, particularly between conservation and extractive development such as mining to inform environmental policy; and to model biodiversity values and ecosystem services for identifying site-level conservation priorities to support action on the ground and policy formulation. I remember a couple of posts over the past three years when my former team and I were exploring species distribution models and learning radar remote sensing, and when we combined these approaches together to identify spatially explicit areas of high conservation value.

By working with a multi-disciplinary team, we had been successful in designing integrated approaches for science-based ecological assessments that recognise the importance of geospatial technologies, which in turn had raised awareness of and informed conservation efforts by local authorities and communities. Remote sensing technology enabled us to map and analyse forest habitat changes for delineating conservation hotspots, guiding forest restoration initiatives, and supporting the development of forest monitoring systems. We also helped develop capacities of partner organisations on using geospatial software tools for protected area management, spatial conservation planning, and forest resources monitoring. These efforts were all aimed at contributing to bridge the research-implementation gap, and in all these an interdisciplinary approach was key.

And over the last fifteen years, that has been my career and, honestly, my personal mission that continues to this day. New technologies alone cannot conserve biodiversity no matter how these technologies improve conservation efforts by making it easier, faster, and cheaper to monitor threatened species and their habitats. That piece of advice I’ll heed from Dr Stuart Pimm, also a professor at Duke University and the lead author of the study. He goes on to say [2]:

The challenge is to use technology more wisely, connect different technologies and get appropriate technologies at the hands of those that use them more effectively. […] If we are to stem the current massive loss of species and ecosystems across the land and the oceans, we need to be much smarter and to engage many others to develop new approaches to the problems.

References:

[1] Pimm, SL, S Alibhai, R Bergl, A Dehgan, C Giri, Z Jewell, L Joppa, R Kays, S Loarie. 2015. Emerging technologies to conserve biodiversity. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 30(11):685-696. [DOI]. * In case you wish to read the paper but are unable to access it through a paywall, you can alternatively access the article in press copy.

[2] Office of News & Communications. 2015. Using–and sharing–new technologies is key for conservation. [URL]; accessed on 10 January 2015].