The Diwata microsatellite and its potential for conserving Philippine biodiversity.

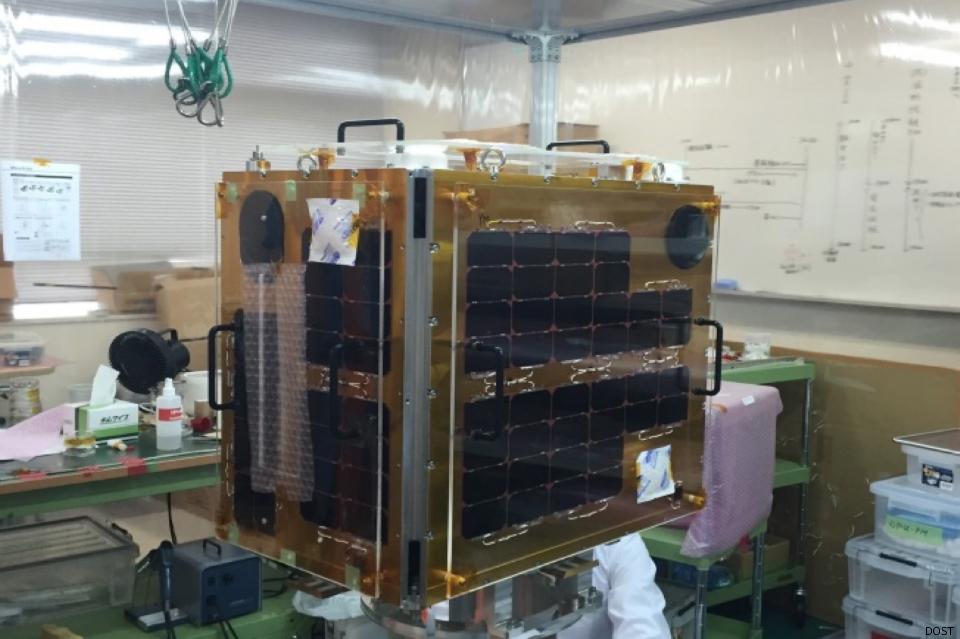

Diwata, the first Philippine microsatellite. (Photo by Cez Versoza [1])

Diwata, the first Philippine microsatellite. (Photo by Cez Versoza [1])

News about Diwata, the first microsatellite to be launched this year as part of the Philippines’ space programme, has been making the rounds over the internet again the past couple of weeks. Last January 12th, Diwata was finally turned over to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, eventually leading to its deployment from the International Space Station this April. Many are excited, especially Filipinos, including me, to see this endeavour finally come to fruition. At last, the Philippines will finally venture into space.

My interest in Diwata is not only because it marks the beginning of a national space programme, which offers tremendous potential for growth and development, and of course, having that sense of ownership and national pride. While there are many applications envisioned from using Diwata’s imagery, I am keenly interested in Diwata because of its potential capabilities in support of conserving Philippine biodiversity, of protecting its species many of which are in fact found nowhere else in the world, and of managing their habitats, such as forests and coastal ecosystems. But before we dive into the reasons why I think Diwata shows promise, let me take you through some bits of information to get to know more about this microsatellite.

Introducing Diwata.

We know that Diwata, or PHL-Microsat-1, is one of two microsatellites that the Philippines will be launching in 2016 and in 2017 [2]. Diwata falls under the category of microsatellites owing to its dimensions of 55cm x 35 cm x 50cm with a 50kg mass [3]. It is the first Philippine earth observation microsatellite and the first one to be designed and assembled by Filipinos as part of the national government’s three-year (2015-2017) Philippine Scientific Earth Observation Microsatellite Programme, implemented in partnership with Japanese counterparts, Hokkaido University and Tohoku University.

Composed of five project components [4], the development of the microsatellite forms the first component of the entire programme. The second involves the establishment of an operational ground receiving station, the Philippine Earth Data Resource and Observation (PEDRO) Centre in Subic Bay Freeport, Zambales, supported by the third component on the development of the data processing, archiving, and distribution subsystem for the ground receiving station. Fourth, the calibration and validation of the remote sensing instruments, or the Cal/Val phase, is intended to calibrate, test, and improve the measurement accuracy, models, and algorithms for the science data products during pre- and post-launch. And finally, the last component deals with the development of remote sensing data products that can be used for different applications.

Among the practical uses envisaged as a result of the microsatellite programme are improving weather forecasting; better disaster risk management and emergency response; periodic monitoring of agricultural production, forest and land cover change, and ocean productivity; and contributing to matters of national security [2,3].

Potential for conserving biodiversity.

Diwata will follow a low earth, sun-synchronous orbit in space at approximately 480 km above the earth. It is expected to pass over the Philippines four times per day with an average of six minutes per pass, capturing around 900 images in each pass [3]. It consists of the following payloads or instruments, namely [2,5]:

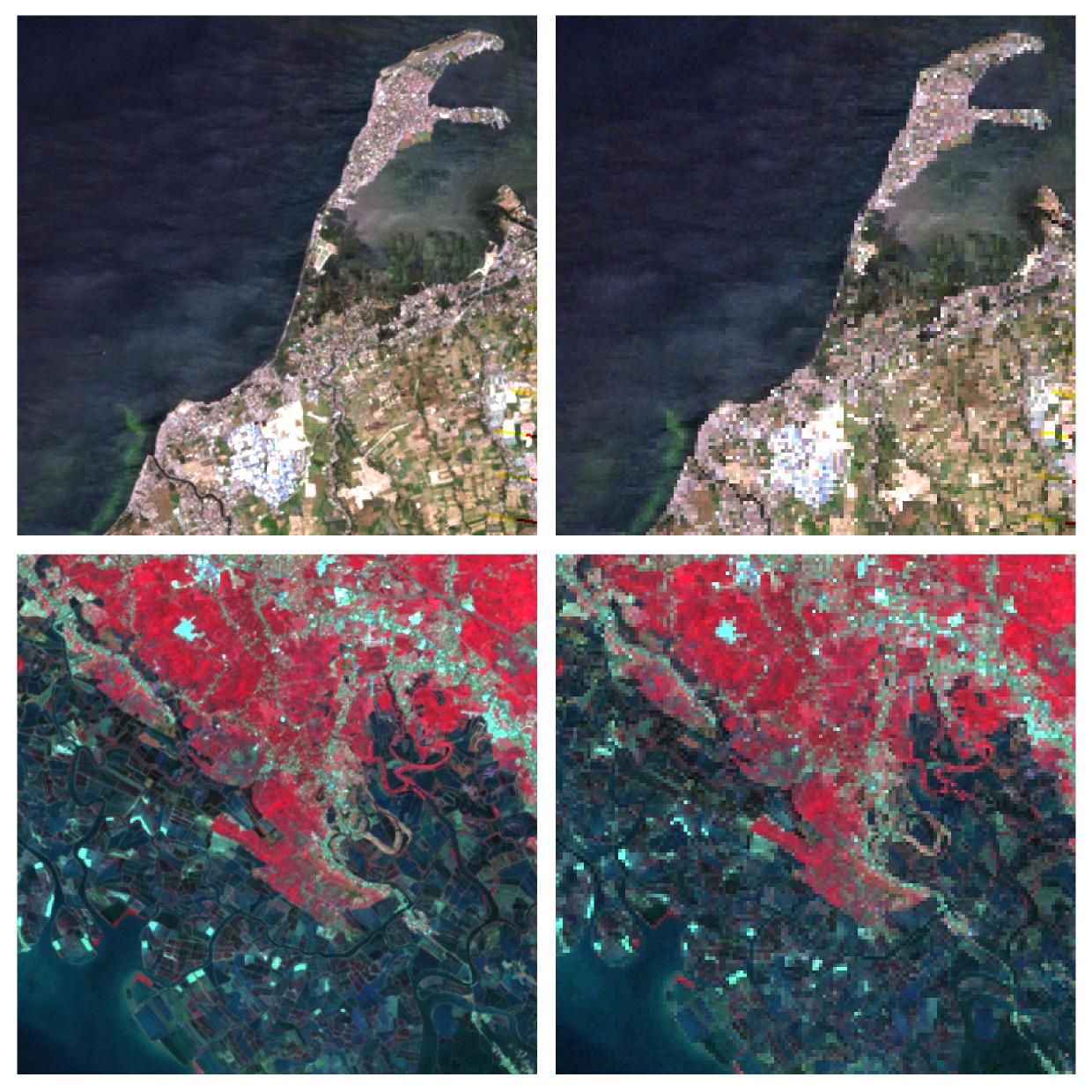

[a] High Precision Telescope (HPT). The HPT instrument will capture very high-resolution images at 3m with each image having a scene size of 1.9km x 1.4km. The images will consist of four bands, particularly the blue, green, red, and near-infrared wavelengths. It will be used for damage assessment from natural hazards such as floods and earthquakes, and potentially useful for monitoring urban sprawl and planning urban development.

[b] Spaceborne Multispectral Imager (SMI) with Liquid Crystal Tunable Filter (LCTF). With a medium-resolution of 80m, the SMI instrument will capture images with scene sizes of 52km x 39km, which will be used for monitoring ocean productivity and changes in vegetation. The instrument also features two optical filters, one for the visible spectrum (420-700nm), and the other for the near- and mid-infrared spectrum (650-1050nm). Another sensor will capture data at the extreme ultraviolet spectrum (10-20nm).

[c] Wide Field Camera (WFC). The WFC will capture panchromatic images with a 7km spatial resolution, which will be used to observe cloud patterns and weather disturbances, and estimate typhoon intensity.

[d] Middle Field Camera (MFC). With a spatial resolution of 185m, the MFC is an engineering payload that will assist in geolocating the images captured by the SMI and HPT instruments.

Both the SMI and HPT are potentially capable of producing data products that can be used for quantifying and modelling biodiversity. And when I say ‘potentially’ I mean it may be able to provide these products given its specs. Similar to the capabilities of NASA’s MODIS or Landsat sensors, the SMI instrument may be used for detecting boundaries of land, clouds, and aerosols; and for quantifying ocean colour, phytoplankton, and biogeochemical properties.

Ecological variables that are useful for quantifying and modelling biodiversity can be measured prospectively, such as land cover for providing a first-order analysis of species occurrence; land and ocean chlorophyll for calculating productivity, plant health, and species diversity; circulation patterns inferred from ocean colour for understanding larval transport; and phenology for identifying species tied to phenological events, among others [6]. Land cover change derived from remotely sensed data permits monitoring the rate of habitat loss, which can be converted into quantitative estimates of biodiversity loss.

One possible limitation of the SMI sensor is its moderate spatial resolution, which is almost three times lower than 30m Landsat data, regarded as the ‘workhorse’ satellite of the world. This drawback, however, can be compensated by the very-high resolution of the HPT instrument, albeit requiring much higher computational processing power due to the large image data sizes. But then, this 80m data is also considerably higher than the spatial resolution of any MODIS data product, hence it could still provide much enhanced products. So if you use MODIS data for your applications, you may want to consider Diwata in the near future.

The WFC instrument, on the other hand, could potentially be used to improve available global data on climate surfaces used for the modelling of species distributions due to its ability to observe cloud patterns. The remotely sensed data could be used for interpolating better climate surface models by complementing existing ground weather stations.

Due to its high temporal resolution at four visits per day, Diwata can also capture images of the Philippines more frequently which may be able to overcome persistent cloud cover that has always been the major limitation in earth-imaging of tropical countries; thereby acquiring more imagery for periodic and temporally consistent monitoring of earth features.

In forest conservation, for example, Diwata’s imagery can be used to monitor forests on a regular basis. Forest clearings can be detected, particularly where these occur in critical watersheds and protected areas, and in turn local government authorities and site managers can use this information to act and implement appropriate measures such as forest patrolling, biodiversity monitoring, or forest restoration. Knowing where forest changes occur can eventually help in understanding why these changes are happening in those areas, and ultimately lead to doing what must be done to address the changes and its impacts. Satellite information can help identify where scarce resources and conservation investments should be directed.

Diwata can potentially supply data to support many of our national government’s efforts to conserve and manage forests such as the establishment of the National Forest Monitoring System. Combined with ground inventories, the remote sensing data can be used for Forest Resource Assessments. Public investments such the National Greening Programme may also benefit from Diwata’s satellite imagery. The 3m image data could potentially provide much needed evidence through periodic monitoring over time of whether reforestation efforts have been successful or not. Data can be used to measure our progress towards achieving global biodiversity targets and whether the Philippines meets its international commitments under the Convention on Biological Diversity or the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+). In effect, it supports good governance by promoting transparency and accountability.

After launch, what next?

Once Diwata is successfully deployed into space and captures its first images of the Philippines, the Cal/Val component is expected to continue through the post-launch phase and the various data science products are developed and distributed to end-users for practical applications.

Dr Carlos Primo David, the Executive Director of the Philippine Council for Industry, Energy, and Emerging Technology Research and Development of the Department of Science and Technology, announced during the 36th Asian Conference on Remote Sensing in Manila last October 2015 that the Philippine government will make the satellite imagery acquired by Diwata open and freely accessible to the public, which will create opportunities for developing various applications of the data. Free and open-access satellite data are key to biodiversity conservation [7].

I am looking forward to accessing Diwata’s image data, which hopefully will be akin to the satellite data access policy or platforms of other countries such as EarthExplorer of the United States Geological Survey, or the Sentinels Scientific Data Hub of the European Space Agency, both of which provide free and open access to repositories of Landsat and Sentinel data, respectively, to anyone interested in utilising these data. I am eager to explore Diwata’s potential for conservation science and research, as well as to document any limitations and to feedback to the science development teams for improving subsequent satellites.

A free and open-access data policy is truly the way forward. As Will Marshall, co-founder and chief executive of Planet Labs, in speaking about the largest constellation of Earth-imaging satellites (or Doves as his company calls it) in human history to be launched into space to capture high-resolution images of every single place on the planet every day, said on the applications of their satellite data [8]:

And we have decided, therefore, that the best thing that we could do with our data is to ensure universal access to it. We want to ensure everyone can see it. We want to empower NGOs and companies and scientists and journalists to be able to answer the questions they have about the planet. We want to enable the developer community to run their apps on our data. In short, we want to democratise access to information about our planet.

He went on to ask his audience, “If you had access to imagery of the whole planet every single day, what would you do with that data? What problems would you solve? What exploration would you do?” If I answered his questions with Diwata in mind, some of the possibilities I mentioned above is what I would be up to.

Finally, the long-term mission should be sustaining the Philippine space programme, and hopefully setting up a Philippine Space Agency to further develop the country’s in-house space capabilities, following in the footsteps of developed nations that have invested in their own space programmes, and even other developing nations that have committed to pursue their own space programmes to contribute to the development of their countries.

References:

[1] Versoza C. 2016. Diwata ascending: the benefits of a Filipino space program. [URL; accessed 12 Jan 2016].

[2] Ranada P. 2015. Introducing Diwata, the first Philippine-made satellite. [URL; accessed 12 Jan 2016]

[3] S&T Media Service. 2015. PHL to launch 2 micro-satellites into space. [URL; accessed 12 Jan 2016]

[4] Electrical and Electronics Engineering Institute - University of the Philippines Diliman. 2015. UP-EEEI hosts talk on micro-satellite technology and PHL-Microsat. [URL; accessed 12 Jan 2016]

[5] Information on payload specifications provided by colleagues and friends from the PHL-Microsat programme.

[6] Turner W, S Spector, N Gardiner, M Fladeland, E Sterling, M Steininger. 2003. Remote sensing for biodiversity science and conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 18(6):306-314. [DOI].

[7] Turner W, C Rondinini, N Pettorelli, B Mora, AK Leidner, Z Szantoi, G Buchanan, S Dech, J Dwyer, M Herold, LP Koh, P Leimgruber, H Taubenboeck, M Wegmann, M Wikelski, C Woodcock. 2015. Free and open-access satellite data are key to biodiversity conservation. Biological Conservation. 182(2015):173-176. [DOI].

[8] Marshall, W. 2014. Tiny satellites show us the Earth as it changes in near-real-time. [TED Talks; accessed 12 Jan 2016]

Additional information from the internet:

Ronda, RA. 2016. April launch seen for Philippine satellite. [URL]

Usman, EK. 2016. DOST, 2 Japanese universities complete Philippine satellite for launching in space. [URL]